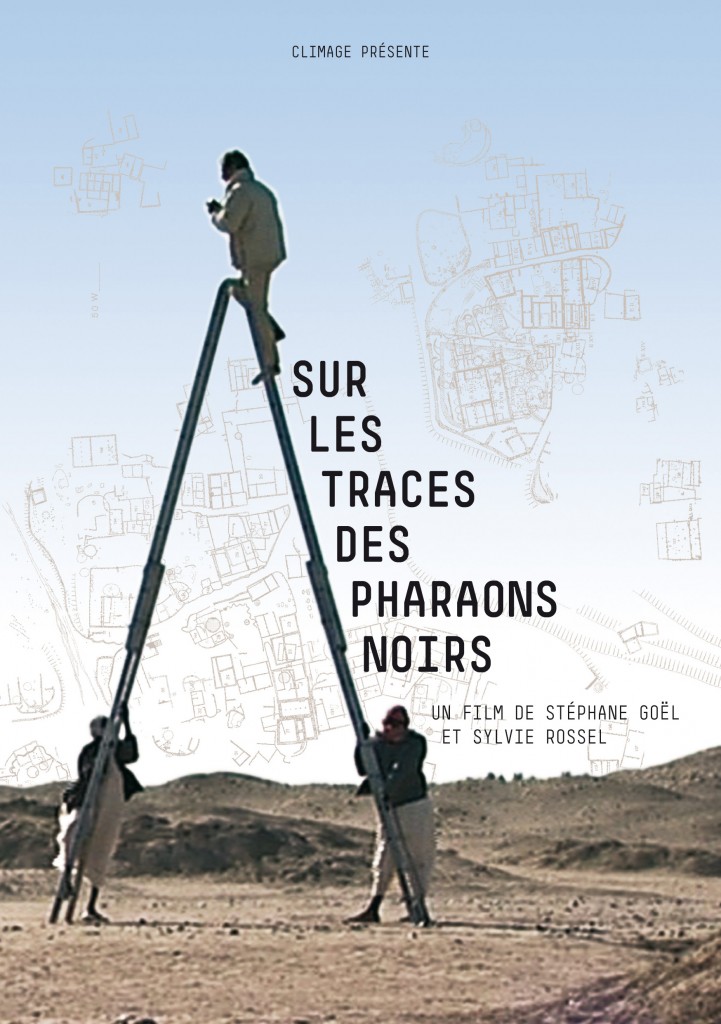

The Black Pharaohs

In 747 BC, Nubian rulers took advantage of Egypt’s weakness to seize the land of the pharaohs. For just under a century, 5 African kings reigned over Nubia and Egypt. Under the reign of these “Ethiopian” kings, i.e. those with “burnt faces”, unified Egypt enjoyed a period of prosperity and artistic renewal. But the Nubian dream in Egypt was short-lived, and the XXVth Dynasty succumbed to the Assyrian and Delta kings. In 664 BC, the last black pharaoh, Tanoutamon, took refuge in Thebes. The battle was terrible: the city was completely destroyed. A king from the Delta, Psammetichus I, was enthroned as ruler of the North and South. From then on, Egyptian kings strove to erase all traces of these black pharaohs, notably by mutilating all statues representing them.

The first man to look into the faces of these kings was archaeologist Charles Bonnet. And the extraordinary discovery he made in January 2003 – a hiding place where seven monumental statues of the Black Pharaohs were buried – underlines the importance of the site of Kerma, Sudan, the capital of the first Nubian kingdom.

Charles Bonnet

Passionate, mischievous beneath his gruff exterior, charismatic as hell, Charles Bonnet divided his life for many years between viticulture and archaeology.

Born in 1933 in Satigny, a village in the Geneva countryside, Charles Bonnet grew up in a family of winegrowers. As a child, he dreamed of Abou-Simbel. His father’s authority obliged him to attend a school of agriculture and then viticulture.

“At a very young age, I became interested in the past, no doubt influenced by my mother, who used to tell me about the Burgundian princesses of our region. My father rightly told me: ‘First learn your trade as a winegrower, and when you can live off your vines, you’ll always be able to do archaeology’, and that’s exactly what I did! When you’re a winemaker or a farmer, you’re very quickly at ease on an excavation site, and I immediately understood how it had to be organized.”

After completing his training as a winegrower, he divided his time between the tractor and university to take a degree in oriental sciences. His first dig was at Choully, where he unearthed the thermal baths of a Roman villa. From excavations to church restoration, Charles Bonnet devotes himself body and soul to enhancing our heritage, forging links between the world of the dead and the living. Appointed Cantonal Archaeologist of Geneva, he was in charge of excavations at Saint-Pierre Cathedral. At the same time as specializing in medieval Christian archaeology, he pursued a remarkable career in Sudan, which also enabled him to become a key figure in ancient Nubian archaeology.

It was chance that brought him to Sudan in 1965.

“A few friends and I had said to ourselves that when we finished our degree we should try excavating in Egypt. It was all a bit romantic, just barroom talk. In the end, we realized that it was very complicated to do excavations in Egypt, that you needed references, an institution, that there were hundreds, thousands of projects and that it would be very difficult to get accepted. So we chose to go to Sudan, again with a touch of romanticism, because Sudan was 19th century Egypt at the time, and it’s still very little visited. There aren’t many archaeological projects in Sudan, even though it’s a very rich and immense country”.

After some trial and error, Bonnet decided to begin excavations at Kerma, a site on the banks of the Nile, 500km north of Khartoum. The gigantic digs he carried out there, lasting three months every winter for the past 40 years, have enabled him to write an entire chapter in the history of civilization.

For much of his career, Bonnet continued to run his wine estate. Funds for archaeology are scarce in Switzerland, and the production of grapes financed much of his work. Some ten years ago, Charles Bonnet handed over his estate to his son Nicolas, one of the finest winemakers in French-speaking Switzerland. They live together in the large family house in Satigny.

Today, Charles Bonnet is showered with honours: Officier de l’Ordre des Arts et Lettres, Member of the Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres, Visiting Professor at the Collège de France, Associate Professor at the University of Geneva, Doctor honoris causa from the Universities of Louvain-la-Neuve and Khartoum, etc. Yet he doesn’t see himself retiring any time soon. At least not until he has completed his major project: the construction of a museum in Kerma to house the fabulous statues of the Black Pharaohs he discovered in January 2003. He owes this museum to the local population, with whom he has worked for so long. To attract a few tourists one day, perhaps, but above all to make the Nubians aware of the richness of their heritage.

“In Sudan, the situation was very delicate. When we started digging, we were very close to decolonization, which took place in 1956. There’s still a sort of inferiority complex. When we talk about ancient architecture and archaeology, we’re told: “Go and see Egypt, that’s where the models are, not here! So we played a more political card and tried to make the Sudanese understand that they had an identity. An extraordinarily rich identity. It’s fascinating to give a population an identity!

The kingdom of Kerma

The existence of an archaeological site at Kerma, a town south of the Nile’s 3rd cataract, was known as early as the 1820s. European travellers who followed the course of the river in Middle Nubia were familiar with the remains of the majestic temple that still stands today, 20m high in the middle of the desert, and which the locals call “Defuffa”. In 1913, the first archaeologist to excavate the site, the American Georges A. Reisner, concentrated mainly on this building and the remains of the few outbuildings surrounding it. He misinterpreted the site as an Egyptian outpost with a commercial vocation. According to him, the Defuffa would have served as a refuge in case of attack and as a residence for the governor of the province. The publication of his findings in 1923 fixed Kerma’s status as an Egyptian city for half a century.

After working for several years on a site called Tabo, Charles Bonnet and his team arrived in Kerma in 1972 to carry out an emergency excavation in an urban environment, 1km from the Deffufa. A construction site had uncovered a curious circular brick well. This first dig enabled Bonnet to appreciate the scale and extent of the remains, and convinced him of the need to concentrate on this exceptional site. This was all the more urgent as the modern town of Kerma continued to expand.

Since then, excavations carried out in a vast area around the Deffufa have revealed the importance of this city a little more each year. Because of the complexity of its organization, because of its size (20 hectares), we can even say that it played the role of a capital. The capital of a fabulous Nubian kingdom which, for more than 1,000 years (-2,500 to -1,500), managed to maintain its independence from its invading Egyptian neighbor. The limits of this kingdom, which is the oldest attested historical formation in Africa, remain poorly known, but its influence was felt throughout the Upper Nile.

Throughout its history, Egypt was irresistibly drawn southwards. It was there that raw materials (gold, ivory, etc.) were to be found, essential if only to ensure worship. Warlike expeditions enabled him to set up trading posts and define a border with the “land of Kush”, which today’s historians call the “kingdom of Kerma”.

At the beginning of the Egyptian Middle Kingdom (2040-1640 BC), the border was fixed at the Second Cataract. The kingdom of Kerma grew in power. The confrontation with Egypt was fierce. This is clearly demonstrated by the construction of a line of enormous fortifications at the cataracts. They reflect the Egyptians’ perception of the danger posed by the Kerma kingdom.

Egypt’s political situation was troubled at this time. The weakening of Egypt was a tremendous opportunity for the kings of Kerma. This was the period of the kingdom’s apogee. The Egyptians were pushed northwards. Around 1600 BC, the kingdom of Kerma extended as far as the 1st cataract, and the Nubians seized the Egyptian city of Elephantine (Aswan).

This period of prosperity was short-lived. Egypt managed to emerge from this period of weakness and entered the New Kingdom (1550-1070 BC). Kamôsis re-established Egyptian influence in Nubia. Amôsis continued this policy. He undertook an expedition south to destroy the “archers of Nubia”. He reached Tombo, 20 km from Kerma. One of his successors, Thutmosis I, reached the fifth cataract. He thus laid his hands on important gold mines. The Nubians finally gave in to these repeated blows. Kerma was taken, destroyed and burned. The children of Kerma’s royal families were taken away to be educated in the Egyptian style. Burial rituals changed. Egyptian ceramics replaced Kerma ceramics.

Within a century, acculturation was complete. Nubian princes even “Egyptianized” their names. So that should have been the end of it. A new phase would begin after the Egyptians had wiped the slate clean. But no: the most incredible thing is that certain Nubian traditions were to re-emerge 800 years later, at the time of the XXVth dynasty – that of the famous Black Pharaohs. It’s as if the culture of Kerma had been maintained, transmitted, whispered, who knows how, from generation to generation…

Charles Bonnet’s work reveals an autonomous, powerful kingdom with strong distinctive features, whose economic and cultural influence is only just beginning to be measured. Today, Kerma is considered a civilization in its own right. While its close proximity to Egypt obviously influenced and even inspired it, it is undeniable that the population developed an identity of its own, independent of that of its neighbor. For some time now, archaeologists have been calling Kerma “Africa’s first great kingdom”.

The statues

After the demise of the Kerma kingdom, the Egyptians founded a new city on the site of its capital for commercial reasons. This city abounded in temples, including a magnificent one in honor of Akhenaten, Nefertiti’s husband. After working on the Nubian city, Charles Bonnet decided to concentrate his efforts on this Egyptian area. And it was here, on January 11, 2003, that the unimaginable happened. The discovery of a real treasure: seven monumental statues of the Black Pharaohs, lying dormant at the bottom of a three-metre-deep hole, forgotten by history for two and a half millennia.

“One detail intrigued me in this area, which I’d been excavating for quite some time,” says Charles Bonnet. What was it? Gold. A flutter of gold leaf on the desert wind, no more than a tenth of a millimetre thick. Like the promise of a buried booty, a golden chamber hidden in the desert sediments? Precious objects? “I started digging. Ten centimetres by ten centimetres. And the further down I went, the more gold leaf I found. Suddenly, my trowel went “tic! I called my French colleague to decipher the hieroglyphs that appeared: “Taharqa” and “Pnoubs”, among others.”

Taharqa is the Black Pharaoh who ruled Egypt and Nubia from 690 to 664 B.C. And Pnoubs? This place name was known from the texts, but no one had yet succeeded in locating it. The enigma was solved: the Nubian city of Pnoubs corresponded to Kerma. Charles Bonnet then realized – to his amazement – that he had stumbled upon the monumental statues of these faceless pharaohs. Buried in this “hiding place”, covered in cloth and gold-leaf plaster, in a pit that must originally have been in a chapel: “Most likely a ritual act, as the sculptures were almost intact.”

Not only does this discovery offer a new key to understanding Nubian civilization, but the remarkable quality and good preservation of the statues, and especially the heads, reveal the faces of these black rulers. All other representations of Kushite kings discovered to date, both in Egypt and in Nubia, had been intentionally damaged: mutilation of the nose is very common and the cartouches have been systematically hammered out. Finally, unlike the often stereotyped representations on sarcophagi, these statues are blatantly realistic.

This is one of the reasons why the discovery of these statues was such an event in the Kerma region. Every day, thousands of people, sometimes travelling more than 400 km, came to the site “just to see”. It was madness,” says Charles Bonnet, “after more than thirty years of trying to interest the local population in my research! We set up a rota system for visitors, who were asked to remain silent so as not to disturb the workers. They watched, fascinated, silent, almost religious. When the statues were brought out, a mass of people applauded wildly as their ancestors passed by. These were their kings, their roots. How can we fail to see in this event the metaphor of a birth, a rebirth even, for this Sudanese people torn apart by war for over 40 years? Charles Bonnet begins to dream: “Perhaps these pharaohs will be the emblematic identity figure that the Sudanese people so desperately need. These powerful kings, who were able to develop the country and defeat the Egyptians, could be for the Sudanese what William Tell is for the Swiss: a symbol of what unites them despite their differences. You know, archaeology is a matter of foreign policy. The French and English have understood this for a long time, but not always in the right way. Reality and a unique discovery prove him right. Forty years of work in the desert will perhaps enable him to make a small contribution to the construction of a national identity in Sudan. And that would be a far greater reward than any academic accolade.