A world in crisis

From the Second World War to the early 1990s, the Swiss Confederation’s agricultural policy was highly protectionist. Although many small farms disappeared in the 1960s, Swiss farmers remained protected compared to the rest of Europe. The Confederation’s price guarantee enabled otherwise unviable estates to support mechanization. However, the number of people employed in agriculture fell during this period, creating a general feeling that farmers were “disappearing”. The need for labor diminished as estates expanded. It was above all the medium-sized farms on the plains that benefited, living out their golden age. An age of certainties too.

However, the turn of the nineties saw a change in the Confederation’s agricultural policy: Swiss agriculture had to keep pace with the world market and become competitive. This meant the end of its privileges and, in the more or less long term, the disappearance of a large number of small and medium-sized farms. What will become of these farmers: food producers, part-time farmers or civil servants? A whole generation of farmers, especially those who have just taken over their parents’ farms, are being forced to invent new ways of working. Trying new approaches to the profession

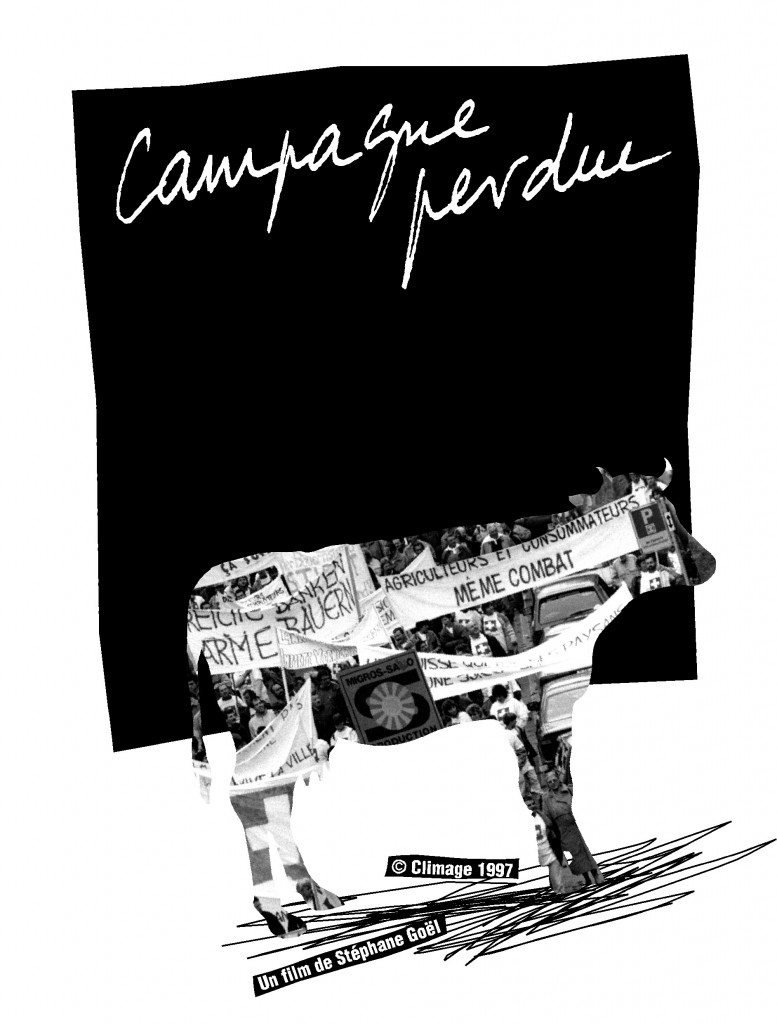

The project

The small Vaud village of Carrouge is home to around ten farmers. Most of them are young people who have recently taken over the family farm. Long-time friends and well-trained professionals, they are determined to do everything in their power to preserve their profession and their way of life. After months of reflection, it became clear to them that the only way out in the long term was through solidarity and the pooling of workforces. The idea of a communal cowshed was born. By pooling their livestock, everyone is relieved of part of their daily workload, freeing up more time to seek other sources of income. The construction of a modern building, adapted to the requirements of integrated production (the animals are able to leave at their convenience and have more space than in small barns), avoids the need for individual investment in farms that are often old and cramped. What’s more, the rationalization of working tools improves the quality and quantity of milk produced.

The difficulties

Even though the six young farmers have known each other for a long time, setting up a collective project is not easy. It comes up against a whole series of habits that need to be challenged, things that aren’t usually talked about. For once, we need to discuss farm revenues openly, put old quarrels and potential conflicts on the table, and think about succession issues. Above all, time is needed to put everything in place, to make sure that nothing is left out, so that no one feels short-changed. Each case is weighed in the balance during endless discussions. In particular, that of the youngest of the six, who has just inherited his grandfather’s small estate and lacks the financial means to invest a sum commensurate with that of the others. What solution will they come up with to enable him to participate in the project, given that the stable is to be built on one of his plots of land?

A revealing change!

As the discussions progress, the protagonists are forced to rethink their place and relationships within the village community. The economic situation is forcing them to question what they have learned and how their parents’ farms operate. In some cases, this leads to friction with their parents, or with other village elders who see this collective project as a form of kolkhoz. They have to show that working together is possible and even advantageous. In a world hitherto renowned for its individualism, the solution appears extremely innovative.

But above all, they had to define their identity and reflect on their place in society, a place that could no longer be taken for granted. The beginnings of the stable coincided with the mad cow crisis and its disastrous consequences for the image of agriculture among the Swiss population. The decision to give priority to cattle embarrassed them, and prompted them to take part in the large-scale farmers’ demonstration in Berne in the autumn of 1996, which ended in violence. The feeling of not being understood prevails.

Director’s point of view

With this film, I want to give a different vision of the rural world. By showing lowland farms, I feel it’s necessary to bring the farmer and his cows down from the mountains where traditional imagery places them. My main interest lies in the desire to understand the cultural changes, the evolution of peasant mentalities, the shift from an individualist conception of work (“the peasant is the only master in his own house”) to a more collectivist conception. The aim is to understand how farmers play with the different images and symbols that society offers them. At the same time, I wanted to convey the emotional aspect of such a transformation, since I come from the village where the film was shot and the protagonists are my childhood friends.

The Carrouge farmers’ project stands out in the classic landscape of Swiss agriculture. But beyond the approach, there are the people, and all these characters have endearing personalities. They are funny, whole-hearted, and hardly recognize themselves in the image of the narrow-minded, bearded, alpine farmer that haunts the mythology of our country. They are between 28 and 37 years old, and their concerns are those of most people. They belong to a pivotal generation and are aware of their responsibility for their children’s future. Will they be able to negotiate this major change without losing their identity? That’s what’s at stake in this experience, and, to my mind, in the film that bears witness to it.