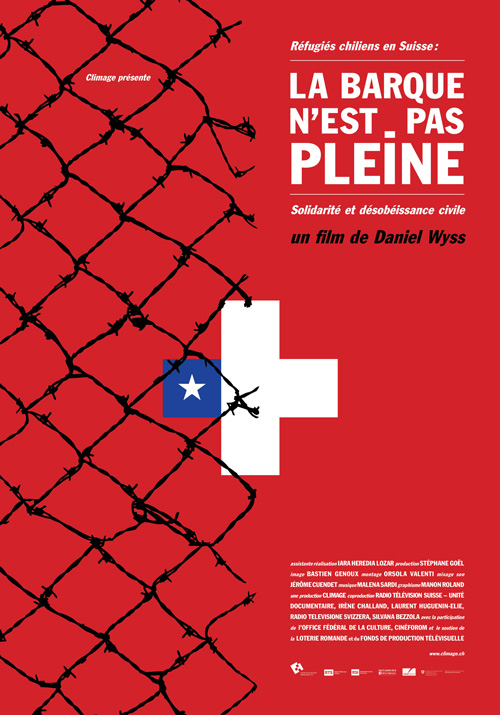

« The boat is not full! »

These were the words of Federal Councillor Kurt Furgler at the press conference he gave in Bern on 5 November 1973 to present the Sonderaktion: the day before, a Swissair DC-8 chartered by the Confederation had landed at Cointrin with 108 Chilean and Latin American exiles on board. They were fleeing the coup d’état on 11 September 1973 by the Chilean military junta. Recalling his predecessor Eduard Von Steiger’s famous metaphor “The boat is full” – used to legitimise the closure of Switzerland’s borders in 1942 – Kurt Furgler skilfully attempted to justify this “special action” (Sonderaktion) to public opinion. He had to reconcile two pressures: that exerted by the far right, which denounced the reception of Chilean refugees, and that exerted by a section of the population shocked by the coup d’état and concerned about the fate of the thousands of Chileans who had been repressed. This gesture by the Swiss authorities – important in comparison with other European countries – was not enough to calm the critics. On the contrary, the authorities’ declaration to admit only 200 Chilean refugees caused an uproar. Between 1973 and 1976, a tug-of-war ensued between the Swiss authorities and the Action Places gratuites movement, a vast citizens’ movement supported by a considerable proportion of the population. In the end, 393 Chilean refugees found refuge in Switzerland thanks to Action places gratuites and 200 thanks to the Federal Council’s Sonderaktion. In the years that followed, Chilean political prisoners also found refuge in Switzerland. The Chilean junta sought to get rid of certain political prisoners by condemning them to exile, and committees in Switzerland lobbied for their release.

After two decades of welcoming with open arms refugees from Hungary (some 14,000) and Czechoslovakia (over 13,000) fleeing the communist regimes in the East, the Chilean refugee episode marked a fundamental turning point in Swiss asylum policy. For the first time, the term “bogus refugees” was used by the authorities in an attempt to restrict asylum policy. The lack of legislation in this area prompted Switzerland to pass its first Asylum Act in 1981.

Flight to freedom

Following the Golpe on September 11 attacks, the military junta declared a state of siege and introduced martial law. Democratic rights such as freedom of expression, assembly and the press were abolished. The violent repression unleashed by the Chilean military extended to anyone suspected of befriending with the democratically elected government of Salvador Allende. In two days, from 11 to 13 September, more than 5,300 people were arrested following raids by the armed forces and police on neighborhoods, villages, businesses and universities. Stadiums – such as the famous Estadio National – schools and conference centres were requisitioned by the military and turned into concentration camps. Opponents were arrested, tortured, deported or executed. In seventeen years, General Pinochet’s military regime was responsible for the death or disappearance of at least 2,279 people; of the one million people exiled during this period, more than 40,000 were political exiles.

In reaction to the events in Chile, a vast solidarity movement developed rapidly on an international scale. Switzerland was no exception. In the immediate aftermath of the coup d’état, several hundred people took part in demonstrations in Swiss towns and cities. For various sectors of the left, the experience of Allende’s Popular Unity was a source of hope and political sympathy: the parliamentary left saw Chile as an example of a peaceful, democratic and legal transition to socialism. As for the extra-parliamentary “new left” movements that had emerged from the upheaval of 1968, they supported this anti-imperialist experiment. Associations in support of the Chilean resistance – the “Allende committees” and the “Chile committees” – were set up in many Swiss towns.

The public outpouring of emotion caused by the coup d’état – far beyond the ranks of the left – contrasted with the restraint and inaction of the federal authorities. Indeed, official Switzerland took a rather positive view of the fall of the Allende government. In Bern, as in Swiss business circles, mistrust of Allende was explained by the fear that Swiss economic interests in Chile would be nationalised. When the coup d’état was announced, the Swiss embassy in Santiago was said to be popping champagne… However, from the very first hours of the coup, hundreds of Chileans turned to foreign embassies to escape the military. Added to this were Latin American nationals (Brazilians, Uruguayans and Bolivians), hunted down by their own military regime, who had found refuge in Chile. The armed resistance by left-wing activists cited by the Junta to justify the repression is nothing more than fiction. Yet the Swiss authorities remained impassive. The press, through 24Heures special correspondent Jacques Pilet, accused Swiss ambassador Charles Masset of closing the doors of the embassy and refusing asylum to people under threat. The controversy over Switzerland’s restrictive attitude towards Chilean refugees is heating up. Pressure from the street, the press, churches, charities and national councillors forced the administration to change its stance. Under pressure, the Federal Council accepted the contingent of 200 refugees channelled through the “special action”, in keeping with the country’s “humanitarian tradition”. However, Kurt Furgler, head of the Federal Department of Justice and Police, and Hans Mumenthaler, head of the new Assistance and Citizenship sub-division, are seeking to leave it at that. Their fears are twofold: on the one hand, the authorities are reluctant to accept communist militants from Chile or Latin America, who are described as “extremists” in most reports. At the height of the Cold War, “red contagion” was a major concern for federal officials. The Department of Justice and Police was particularly vigilant in sorting out refugees from the special action contingent. In addition, the issue of Chilean refugees arose in the midst of a public debate on foreign overpopulation in Switzerland. Furgler feared that taking in refugees could have an impact on the outcome of the second Schwarzenbach initiative “against foreign domination and overpopulation of Switzerland”, which was put to the vote in October 1974 and ultimately rejected by 75% of voters.

Action for free places: from humanitarian impulse to civil disobedience

The quota of 200 refugees under the special action was deemed insufficient by the solidarity movement with Chile. “Action places gratuites”, a citizens’ movement that is spreading throughout Switzerland, is appealing to the public to take in persecuted Chileans. More than 3,000 Swiss families from all walks of life have declared their willingness to take in Chilean refugees in their homes. This appeal was inspired by the “free places” initiative launched in 1942 by Pastor Paul Vogt, which aimed to take in refugees interned in Switzerland in private homes. “Action places gratuites” was born out of the convergence between the Basel-born abbot Cornelius Koch and the “Friends of the Republic of Chile” group, founded in early 1973 by young people from the Longo Maï community in Basel. The humanitarian nature of the action and the efforts of its promoters attracted support and membership from far beyond the left. In Ticino, following a motion, the members of the Cantonal parliament waived their attendance fees and the State Council made CHF 10,000 available to the Chilean refugee aid movement. “Action places gratuites” used this money to bring in Chilean opponents who until then had not needed a visa to enter Switzerland. On 23 February 1974, the first group of five Chileans arrived from Santiago on Swissair’s weekly flight. This was to be the start of a terrible tug-of-war between the federal authorities and “Action places gratuites”. Faced with a “fait accompli”, the Federal Council decided on 26 February 1974 to introduce a visa requirement for Chilean nationals. Pastor Guido Rivoir, who succeeded Abbé Koch in the movement, managed to smuggle in the Chilean refugees. The pastor from Ticino bought plane tickets from his nephew, a travel agent in Turin, for the flight from Buenos Aires to Milan, and then organised the illegal entry of the refugees via Ticino. Action places free of charge, thus circumventing the visa requirement. Between 1974 and 1975, Federal Councillor Furgler and Pastor Rivoir met or wrote to each other regularly, but were unable to reach an agreement on accepting more refugees. Mr Furgler tried to discredit the movement in the eyes of the press, but to no avail. In 1976, financially exhausted and subject to political pressure, Action places gratuites put an end to its activities. This “solidarity from below”, almost unique in Switzerland, had helped more than 2,000 people to leave Chile and come to Switzerland.

40 years on

For Chilean refugees in Switzerland, the transatlantic journey to Switzerland marked the beginning of a long exile. How did they integrate into their new host country? Prohibited from engaging in politics on their arrival in Switzerland, and systematically registered by the police, the Chileans nonetheless established relations with networks active in Switzerland and continued to denounce the Chilean Junta. However, the delicate issues of exile and the possibility of returning to Chile still haunt them. Over the years, the Chilean exiles have come to realise that they are not “in transit”, but have put down roots here. The many cultural events organised by their communities bear witness to the fact that they are part of our daily lives. Many of these exiles have settled permanently in Switzerland. However, in the early 1990s, during the country’s “democratic transition”, several hundred Chileans attempted to return home. For some families, the return went more smoothly than expected, particularly for the “secondos”, children who had spent their youth and schooling in Switzerland, and who found the return a heartbreaking experience.

The children of Chileans exiled in Switzerland rediscovered their history in 1998. Augusto Pinochet, retired and a senator for life, was arrested in London following an international complaint lodged in Spain. Put under house arrest, he was released for health reasons in March 2000 and returned to Chile, where he died in 2006, before the legal proceedings against him had been concluded. For the exiles, the work of justice and remembrance continues to this day.