The history of the Ecuadorian railroad

Before the railway was built, and during the early years of the young Republic of Ecuador, power was divided among a handful of clans. The biggest – Manabi, Guayaquil, Loja, Quito and Cuenca – had already taken turns in power. With each change of power came a complete change of cabinet and senior civil servants, all eager to grant themselves a few personal advantages. Nepotism often led to intense regionalism and infighting, often resulting in bloodshed.

In 1855, Latin America’s first train was built in Cuba. Astonishment mingled with awe at such a monster belching fire and smoke. Until then, Ecuador had essentially been an Andean country with one port. Indeed, the Spaniards had only built the port of Guayaquil and had no interest in the coast. On the one hand, to avoid the swamps and thus tropical diseases, and on the other, because the Indians, and therefore the workforce, lived mainly in the Andes. For Garcia Moreno, conservative president of Ecuador between 1868 and 1880, the train’s natural route was from the capital Quito to Guayaquil, while remaining in the Andes for three-quarters of the journey. In 1875, Garcia Moreno began building the first 25 km from his native Guayaquil. In those days, a journey between Quito and Guayaquil (450km) took 15 days!

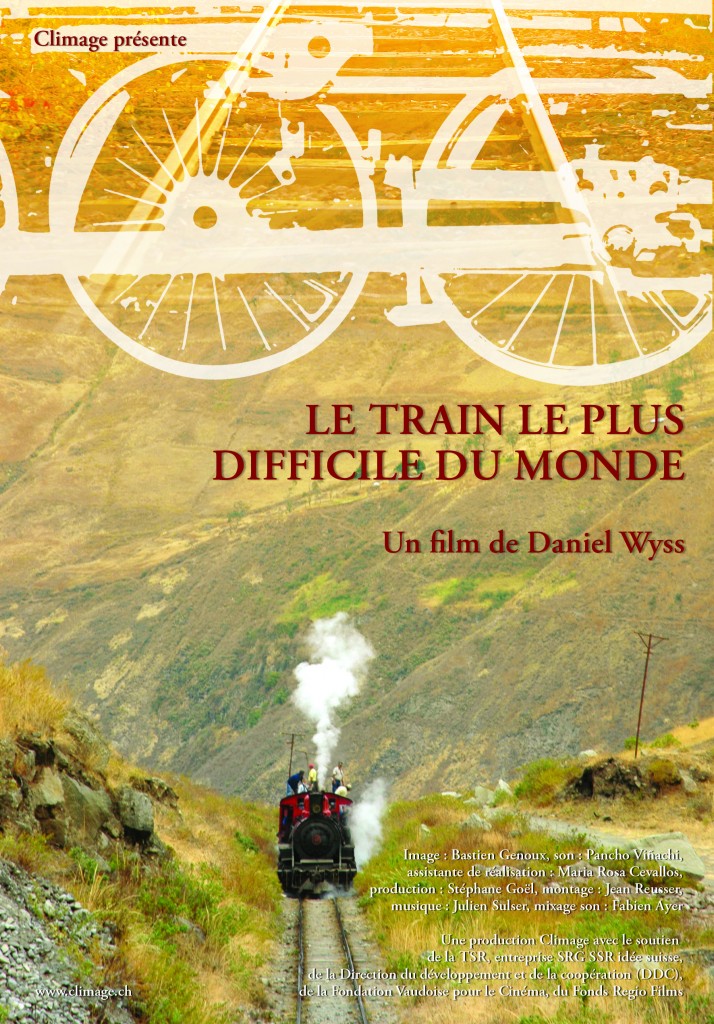

In 1890, President Eloy Alfaro contacted North American technicians Archer Harman and Edward Morley. In view of the altitude difference and the quality of the terrain, Harman called the railroad “the most difficult railway in the world”. The deal was struck, and the Guayaquil & Quito Railway Company began construction in 1899. Alfaro inaugurated the line in 1908. Thus was born the idea of nationhood and the integration of the country’s different regions. Trade between the coastal and Andean populations grew up around the railroad.

For more than 70 years, this line operated until it reached 30 daily convoys in each direction. The railroad became an unprecedented trade route. Connecting tracks were built to link the main rice, banana and sugarcane production centers.

Construction of the railroad between Sibambe and Cuenca (the country’s 3rd largest city) began in 1915. Construction of this 150km stretch took almost 50 years. It was only operated for 20 years. Successive governments have appropriated the rails for iron recycling. The last rail recycled was used to build trenches during the war against Peru in 1996! The flattening of the land has often been used to build roads.

With the semi-privatization of the railways in the 1960s, the long decline of the railroads began. The government never carried out the maintenance work needed to preserve this heritage. Ecuadorians know that the train is a political booty. Politicians have systematically supported the rehabilitation of the train. Once elected, governments put their own men in charge of ENFE. The latter came with innumerable assistants and secretaries, whom he was quick to hire. In this way, the public service became completely bureaucratic, undermined by an excessive number of employees, many of them agents who were only interested in getting paid.

Nature dealt the fatal blow. In 1982, heavy flooding cut the line. The government ordered the tracks to be rebuilt, but economized on the work, making the new sections fragile and, in the event of rain, prone to derailment. The government always blamed the narrow gauge (1.07m vs. 1.20m in Switzerland) as the reason for abandoning the railroad. It’s true that this gauge was a valid solution in 1900. Today, it prevents trains from going fast (35km/h). The “el niño” phenomenon in the winters of 98 and 99 once again cut the line. The port was forever separated from the capital. The line has never been fully restored.

For ENFE (Ecuadorian Railways), the solution lies in building a new track with a standard gauge. The Brazil-Amazon-Ecuador-Asia Pacific axis, and the construction of a Manaos-Quito-Guayaquil line, had been studied by a Canadian team. What seems like a utopian dream is the spearhead of Sergio Coellar, former manager of ENFE. For Coellar, this section would put Ecuador back at the center of the Latin America-Asia trade route.

The cost of rehabilitating the old tracks was put at $500 million. Supporters of the train are now mobilizing to try and get private individuals to sponsor sleepers. The train’s agony cannot be halted so summarily. Using the track for tourism could save the train. At least, that’s what the proponents say, taking the example of the Cuzco-Macchu Picchu train in Peru. Rehabilitating the train would have a direct impact on 70% of Ecuador’s population, including all those regions that have no direct access to the train but use this means of transport in coordination with other river and land-based means.

While it’s true that these regions have other means of transport, especially buses and trucks, these services lack the means for mass transport, and are subject to perpetual fare hikes that mainly affect the poor. So it’s the poorest sections of the population who need the train most, especially agricultural workers who use it to transport their produce. By transporting their produce at low cost, they can sell it on the market at a better price.

Since 1982, when the Quito – Guayaquil line began to decline, there has also been a significant increase in migration between the countryside and the two major cities. Between 1982 and 1990, the percentage of the rural population leaving the countryside rose from 5.4 to 12.1%.