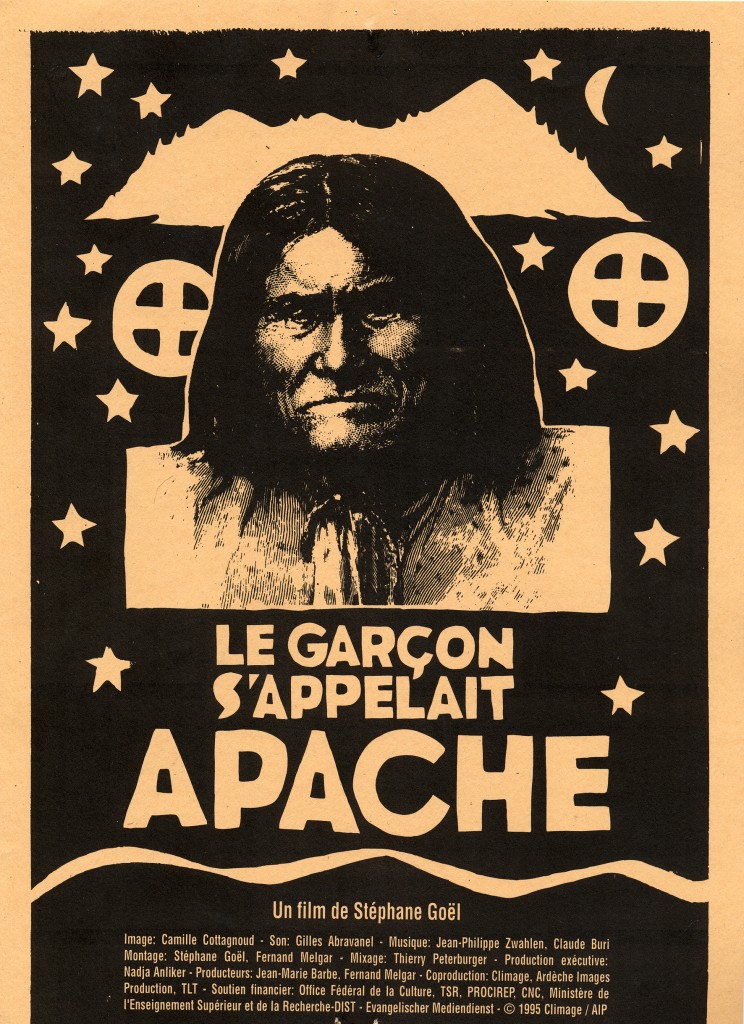

The mountain

For the Western Apache, Mount Graham in Arizona is a sacred mountain – the source of life, where Usen (or Yusn, God) taught them the original knowledge that became the foundation of a complex religion. It’s a place where people’s prayers can ascend to heaven, a place where secret, unchanging rituals are performed.

This mountain, however, does not belong to them. Located outside the San Carlos Apache reserve, it has been abandoned to logging for over a century. Nevertheless, its summit remains untouched by civilization. The harsh climate and steep slopes discouraged settlers.

Mount Graham rises to over 3,000 meters above the arid Sonoran desert. Its summit is covered by a dense forest, the likes of which can be found in northern Canada. More than 18 species of flora and fauna, unique in the world, are trapped on what American ecologists have dubbed “the island of heaven”.

Today, a vast construction site unfolds at the top of the mountain. Armed men keep a 24-hour watch on the construction of an astronomical observatory financed by the Vatican, the Arcetri Institute in Florence, the Max Planck Institute in Bonn and the University of Arizona.

The observatory

It all began in the late 70s. The University of Arizona was developing a new technology for manufacturing telescope mirrors. This led scientists to look for a suitable location for a newly conceived astronomical observatory, which would bring together several telescopes in a complex unique in the world. The site of Mount Graham, with its pure, dry summit air ideal for stargazing, was chosen at the dawn of the 80s. The Mount Graham International Observatory is to comprise 7 telescopes on two sites. Two telescopes have already been built: the H. Hertz Telescope, a 10-meter radio telescope, and the Vatican Advanced Technology Telescope. The Large Binocular Telescope (LBT), a gigantic pair of binoculars with two 8-metre mirrors, will be the world’s largest telescope, and is scheduled for completion in 1996. The other 4 projects are not yet well defined.

The Vatican

Since the 16th century, when Pope Gregory XIII reformed the calendar, the Vatican has been interested in astronomy. Despite the conflicts that pitted the Church against scientists, of which the Galileo controversy remains the best-known, Pope Leo XIII founded the Vatican Observatory in 1891.

After setting up its telescopes behind St. Peter’s Basilica, then at Castel Gandolfo, the “Specola Vaticana” opened a research institute at the University of Arizona in 1981 and joined the Mount Graham development project.

The “VATT” (Vatican Advanced Technology Telescope) optical telescope is a small telescope, 1.8 meters in diameter, whose mirror is built using a new technology developed by the University for the construction of the giant telescopes of the future, including the LBT. The mirror for this telescope is a prototype that was donated to the Vatican, which then only had to finance the body of the telescope and the building that contains it.

The “Specola Vaticana” is staffed by a dozen Jesuit researchers who are particularly interested in the existence of other solar systems that could harbor living beings. According to Father George Coyne, director of the Specola, the discovery of such extraterrestrial life would pose a theological problem: Are these beings human? Have they experienced original sin and redemption?

Opponents

As early as the mid-80s, a coalition of environmental groups (Sierra Club, Audubon Society, Earth First!, etc.) formed to try to halt the project’s progress. The environmentalists criticized the impact of the observatory on a preserved site that is home to a number of rare and endangered species (including the endangered Mount Graham red squirrel). Their actions in the courts and on the ground monopolized media attention and concealed the emergence of another opposition movement: that of the San Carlos Apaches, who perceived the construction of the observatory on their sacred mountain as a desecration.

The Apaches

In 1991, before construction began, the San Carlos Apache Tribal Council passed the following resolution:

“- Whereas for generations our elders have instructed us in the sacredness of dzil nchaa si an, also known as Mount Graham, and its vital importance in preserving our traditional Apache culture;

– Whereas this mountain is absolutely essential in the physical and spiritual healing rites practiced by our medicinemen, as well as for the learning of their religious knowledge;

– Whereas any permanent alteration of the present form of this mountain is a mark of profound disrespect for a revered part of our ancient lands, as well as a serious violation of our traditional religious beliefs;

– Whereas, the planned destruction of this mountain will contribute directly to the destruction of fundamental aspects of Apache spiritual life;

Therefore, the San Carlos Apache Tribe declares its firm and total opposition to the construction of a telescope on the summit of Mount Graham as well as its determination to defend its constitutional rights if this project is allowed to continue.”

The Apaches have formed the “Apache Survival Coalition” and are filing a lawsuit in the US to assert their right to the free exercise of their religion, as guaranteed by the First Amendment to the Constitution.

Their spokesmen, Ola and Mike Cassadore-Davis, have been criss-crossing Europe and the United States for the past two years in search of support. They would also like to meet the Pope to remind him of the encouragement he gave them during his visit to Phoenix in 1987: to do everything to “preserve and keep alive” their culture, language, values and customs.

The Apache religion, damaged by centuries of war and oppression, has fewer and fewer followers. However, Mount Graham can serve as a catalyst to mobilize young Apaches in their claim to belong to a noble and ancient culture. The members of the Coalition see this as an opportunity for their people. They are about to wage a battle which, in their eyes, could well be decisive in the future relationship between Western and indigenous culture.

The director’s point of view

The story of Mount Graham came to light during the shooting of my latest film, “West of the Pecos”. The Mescalero Apaches I met on that occasion shared with me their concerns about the desecration of the sacred mountain of their San Carlos cousins. Beyond the simple conflictual aspect of this situation, I felt it was important to show how history repeats itself. The Apaches are emblematic of the indigenous peoples whose identity our Western civilization denies. All those whom we have taken to heart to massacre for centuries, and who are still victims of humiliation and deculturation.

The gulf between Indian and Western worldviews remains gigantic, and seems far from being bridged. In the case of Mount Graham, for example, the observatory’s promoters never took the trouble to conduct a serious survey on the reserve or to explain their project clearly and simply to the Apaches.

The Mount Graham conflict is indicative of this difference in perception. It is a point of convergence between three modes of thought: scientific rationalism, Christian dogmatism and Apache holistic spirituality. No matter who’s right in this conflict, it’s all a question of point of view. What concerns me is the lack of communication and the inability to take into account a non-rational conception of the universe. It’s a question of respect, a fundamental right to be different.

Whether we like it or not, the spirit of the Apaches will forever blow over a land that, as the great Chief Seattle said, we don’t own, but to which we belong.

Stéphane Goël – 1995