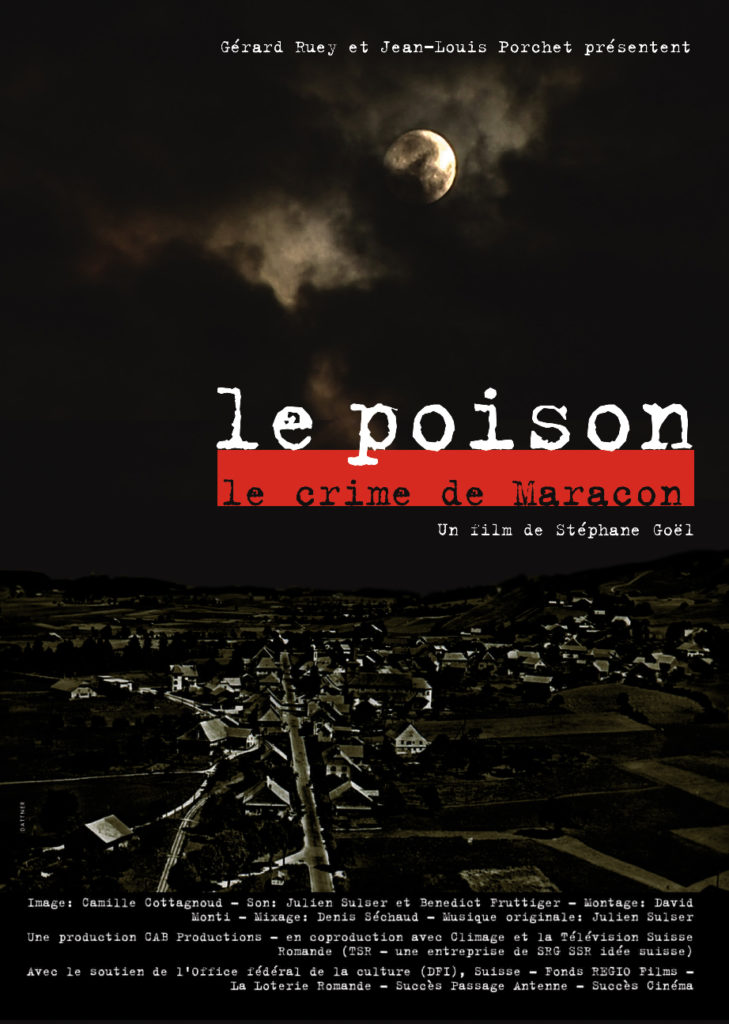

June 19, 1949, at 2105, by tf.

Cpl Pache, head of the Oron post, informs us that the bodies of two women have just been discovered in a wood beside the Ecoteaux-Semsales cantonal road, in Maracon (VD). This must be a double crime. This sof., who was informed of the above by gdm. Pahud, of the Palézieux-Gare station, immediately went to the scene. He has been unable to give me any further information for the time being.

Thus began one of the most mysterious criminal cases in French-speaking Switzerland. On June 19, 1949, two young girls aged 17 and 18, Marie-Thérèse Bovey and Hélène Monnard, were brutally murdered in a small wood near the village of Maracon. Leaving vespers in Semsales, they were walking to the Bossonens soccer club fair. On this fine Sunday afternoon, many people were walking and picnicking in the area, but none of them heard the shots that ended the lives of the two women.

At around 7:30 pm, a farmer from Rogivue discovered the bodies below the road and alerted the police. The gendarmes initially thought it was a traffic accident, but informed the cantonal police commander. The bodies were not removed until the following morning. On the table in the Maracon town hall, the doctor extracted two 6mm bullets from the victims’ bodies. There was no apparent motive: the girls had neither been raped nor robbed. Although they were from Fribourg, as the bodies were found on Vaud territory, the case was investigated by the Lausanne police.

From the outset, the investigating magistrate established a link with an event that had taken place in the region a month earlier. On Sunday May 8, a young girl from Semsales, Josette M., was attacked by an unknown man on the same road. After shooting her in the back, the man raped her. She was a poor girl, and there was little interest in her misadventure. It wasn’t until the crime of June 19 that she was really taken seriously: was she the killer’s first victim? Was the weapon used the same? At the request of the police, the hospital agreed to a discount to extract the bullet still lodged in her back, for comparison with those that had caused the deaths of the two walkers.

In the days that followed, the description of Josette M.’s assailant was widely circulated: a thin, grizzled man riding a black bicycle with bunches of daffodils hanging from it. The man was never found.

The crime made the headlines. Soon, journalists, amateur investigators and curious onlookers were prowling the area, complicating the work of the police. Rumors spread quickly. Tempers flared, and within weeks paranoia was at its height. Hunts are organized. Everyone suspects everyone else. People talk nonsense. Enticed by the promise of a 1,000-franc bonus for any information leading to the solution of the enigma, many citizens take on the role of Sherlock Holmes, investigating on their own account on neighbouring farms.

The fever spreads, and soon the whole of French-speaking Switzerland is holding its breath as the press reports daily on the progress of the investigation. Murderers were seen everywhere. The slightest deviance became suspect, the slightest out-of-the-ordinary behavior a source of anxiety. Dozens of letters of denunciation reach the police, who investigate each case. They are especially interested in deviants, social cases and trippers, believing that crime is the work of the deranged. They even contacted Scotland Yard to question a mysterious English original “in shorts” who had been seen in the area on the night of the crime, and who turned out to be an innocent hiking tourist.

By autumn 1949, the culprit had still not been found. The investigation stalled. Cooperation between the Vaud and Fribourg police forces was problematic. In Semsales, people speak patois when they don’t want to be understood by people from Lausanne. The case promises to be bogged down for a long time. It will last twenty years.

Twenty years that will leave a lasting mark on the region. The lack of any apparent motive and the slowness of the investigation led to wild speculation. In the eyes of the police and many journalists, the murder could only be the impulsive work of an unbalanced person. The public, on the other hand, saw the delay in the investigation as proof that the crime had been committed by a “fat man”, a local notable. The murderer would benefit from powerful protections preventing the police from doing their job properly: was one of the girls impregnated by someone from another social class? Or did she know too much about a shady affair involving some powerful local? Public rumors point the finger of blame at the parish priest, the mayor, the prefect, the gendarme…

By spring 1950, tension was at its height in Semsales. The population demanded justice. Every evening, hundreds of people gathered in a long procession through the village streets, even staging the murder on horse-drawn carriages. Stones are thrown at houses housing witnesses suspected of keeping silent. Firecrackers explode in the vicarage garden. Masked men threaten the family of a presumed culprit. In desperation, the mayor calls in the army to calm the situation.

After questioning hundreds of witnesses and detaining dozens of suspects, the police bitterly admit their powerlessness.

For many years to come, attempts will be made to ensure that the affair is not silenced once and for all. The Maracon crime aroused the passion of a few enthusiasts who tried to solve the mystery. In 1980, Gérard Bourquenoud, a former policeman turned journalist, published the results of his lengthy investigation in “Fribourg Illustré”. He claimed that the murder had been committed by two men from Semsales, one of whom was a prominent citizen. Without mentioning them by name, he provided clues to their identity. The outcry was immediate, and the region caught fire as it had 30 years earlier. Insults flew, as did threats of revenge. Bourquenoud was convicted of libel.

Since then, newspapers have stopped writing about Maracon. Today, the last remaining witnesses are gradually disappearing. The general public may have forgotten all about it, but the memory of those twenty years of unfinished research is still fresh in the minds of many old-timers. The gloomy atmosphere surrounding this tragic event took a long time to dissipate. Fifty years after the fact, the vague rumours that remain are still the same: “It was the priest who did it”, “The case was hushed up, the culprit protected”, and so on.

The police file will soon be in the public domain and transferred to the Vaud cantonal archives. Thousands of pages thick, it reveals the extent of the work accomplished by the various police departments. It also disproves many of the rumors that have plagued the region for so long. Above all, it paints a candid portrait of an era and a country. As such, it is an invaluable sociological document. This tragic event brought to light the tensions, fears, prejudices and hidden conflicts of a rural society that was still very isolated, where rumors could fuel class hatreds, all the more so as news was exchanged orally in the bistro or in the village square after mass. The differences in mentality between Waldensians and Fribourgois, Protestants and Catholics, rivalries between members of different political parties, and jealousies between peasants all come to the fore. This crime reveals all the fantasies and phobias of an era: from the fear of outsiders, prowlers, the destitute, basket weavers and foreign tourists, to the hatred of the powerful.

Fifty years after the event, the region has changed enormously. Maracon and Semsales are populated mainly by commuters working in Lausanne or Fribourg. These newcomers have hardly heard of the affair that made headlines in French-speaking Switzerland. But the small white cross nailed to a tree where the bodies of the two girls were found still stands. It reminds curious walkers that justice has not been done and that an entire country has not been able to mourn.